How India Can Prevent the Next Oxygen Shortage Crisis

With access to oxygen, India will never have to suffer from asphyxiation again. The COVID-19 pandemic has been sweeping the globe since January 2020 in waves of variable severity. Still, oxygen is the only treatment for COVID-19-induced hypoxaemia, an unusually low blood oxygen level brought on by a variety of fatal lung disorders. Organs and tissues start to fail as blood oxygen levels drop, necessitating an urgent need to start patients with severe COVID-19 on supplemental oxygen.

The daily need for additional medical oxygen in India increased to almost 12 times what it was before to COVID-19, with a disastrous effect throughout March, April, and early May of 2021 due to a devastating second wave of coronavirus across India. The health sector was simply unable to quickly ramp up critical care, to provide oxygenated hospital beds, ICUs, medications, and ventilators, much less back up supplies, due to long-term neglect and chronic underinvestment.

Existing hospitals and crematoriums were completely flooded and overburdened due to the enormous demand for oxygen that surpassed the immediate supply. However, certain state governments, most notably Kerala, had made advance plans and overall kept an excess of oxygen.

Most oxygen disasters across India could have been avoided.

In India, the majority of oxygen disasters could have been prevented. This blog discusses India’s present system for providing medical oxygen, covers the response to oxygen crises, including the issue of severe oxygen shortages in several Indian states, and offers suggestions for how India might stop the next catastrophe brought on by oxygen shortages.

What is the current model of medical oxygen supply?

Both private and public hospitals in India currently purchase medical oxygen from the market. This process functions relatively effectively during “peacetime,” that is, during periods of typical and little varying daily demand, except when there are significant governance shortages (as in Gorakhpur).The absence of sufficient controls and stewardship in market systems, however, results in unintended outcomes in the face of a fierce and widespread epidemic.

As a result of supplies being fixed in the very near future, prices could increase dramatically, making oxygen unaffordable and increasing the mortality rate among the very poor. other possible results include hoarding in anticipation of future price increases, which would result in the same result. We have, sadly, seen all of this. There are logistical and geographic issues as well.

Off-site production of medical oxygen for medical application averages 4000MT per day and is mainly centred in eastern India.The COVID-19 pandemic’s record number of deaths from preventable oxygen shortage has brought attention to how flawed and ineffective the present medical oxygen delivery system is.

What led to the problem of severe oxygen shortages in some Indian states?

India needed around 8000 metric tonnes of medical oxygen per day during the COVID-19 crisis, therefore the central government tried to replace the market with a hurriedly devised mechanism. The central government took over the distribution of the available medical oxygen supplies, while a sizeable portion of industrial oxygen was channelled towards a higher supply of medical oxygen and exports were outlawed. According to some formula based on the number of oxygen beds and ICU beds, the oxygen allocations to the various states were made.

According to this plan, the states would schedule distribution to both public and private hospitals under their control. The foundation for such distributions was at first imprecise. The overly centralized reaction and use of a set formula for allocations lacked flexibility as the second wave of COVID-19 crested in several states at various times.

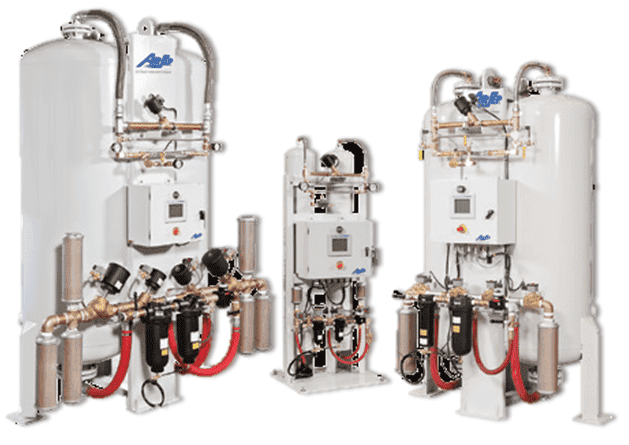

The variable frequency of COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations, and life-threatening situations were not monitored or taken into consideration. It took eight months for the Indian government to award the contract for the construction of 162 pressure swing adsorption PSA plants at the district level, which are facilities with equipment that can condense oxygen from the air for government hospitals. only 33 PSA plants have been erected as of the time of writing this blog (and not all of them are operational), leaving the majority of facilities dependent on outside supply.